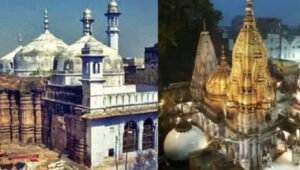

In the recent ruling of the High Court, the court dismissed the Muslim side’s plea on the Places of Worship Act, 1991 in the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvyapi dispute and ruled that the suit filed by Hindu sides claiming ownership isn’t barred by the PoW Act, by allowing limited puja practices in specific area within the Gyanvyapi complex by the Hindus.

However, after the ruling, the controversial act has again come into limelight with the constant debates and deliberations around whether Allahabad HC’s verdict infringes on the Act or not.

Thus, in this article, we’ll delve into the significant exemptions of the Places of Worship Act, 1991 in the light of the ongoing Kashi Vishwanath temple-Gyanvyapi mosque dispute.

About the Places of Worship Act

The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, of 1991 is a significant legislation that maintains religious harmony and prevents disputes by prohibiting the conversions of any place of worship and to provide maintenance of the religious character remains as it existed on August 15, 1947.

Moreover, the PoW Act was enacted in 1991, during Narasimha Rao’s tenure as the Prime Minister (1991-1996). This period coincided with the peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement in 1992, as this Act aimed to prevent religious disputes and maintain communal harmony. Rao, despite facing criticism from both Hindus and Muslims’ side, prioritized national peace and unity by pushing for the Act’s enactment. However, the Act consists of certain prohibitions that need to be addressed.

Prohibition of the Act

The Section 3 of the Act prohibits the conversion of any place of worship, whether fully or partially. This includes the changes or alternatives of any nature meant to change the religious character of the site to prevent disputes and promote peace by freezing the religious characters of the place of worship as it existed before August 15, 1947. Like in the Ram Janmabhoomi- Babri Mosque dispute, because it was built in the late 19th century.

Further, Section 6 punishes whoever violates the prohibition on conversion under Section 3 for imprisonment of three years or a fine. And, Section 8 originally dealt with the power of the central govt to exempt certain places of worship from the Act’s purview. But it was repealed in 1999 and is currently irrelevant.

Maintenance of Religious Characters

The Section 4(1) of the Act, states that the religious character of any place of worship shall be maintained as it existed on August 15, 1947, which mandates that no one can change the status quo of a religious site established before this date. Besides, Section 4(2) abates (ends) all the legal proceedings on the conversion of places of worship that were pending as of September 18, 1991, when the Act came into success.

Furthermore, these provisions apply to all the ‘places of worship’ including temples, churches, mosques, monasteries, gurudwaras and other sites designated for public religious worship, along with covering both changes in rituals and physical alterations that could fundamentally alter the nature of the site. However, due to some exemptions that exclude certain situations or entities from the application of the Act.

Exemption of the Act

The places protected under the Ancient Monuments and Archeological Sites and Remains Act, of 1958, are excluded from the PoW Act. This means that the Act’s prohibitions on conversion and maintaining the religious character as of 1947 don’t apply to these protected sites and ensure historical and cultural preservations.

Besides this, the Act doesn’t apply to cases where parties have already reached a mutual agreement regarding the place of worship before its enactment on September 18, 1991. Also, any changes in the religious character of a place of worship that occurred before September 1991, are not affected by the Act. However, this Act came again into the spotlight in the ongoing case of the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvyapi dispute.

Current Debate and Outcome

The current ongoing Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvyapi Mosque dispute has brought the PoW Act, 1991 into the limelight, raising questions about its applicability and interpretation in cases and histories inquiry in certain situations. While debate surrounds the balance between preventing communal tensions and addressing historical injustices within the Act’s framework.

Overall, the outcome of this dispute and similar cases will set an example for interpreting and utilizing the PoW Act in future disputes concerning religious sites and historical claims, with significant implications for similar cases across India.

Comments 1